Recording

The Big Anchor Project recording system allows you to record as little or as much as you like.

Just add a photograph and a location to achieve a Bronze record, identify features on your anchor for a Silver record or measure your anchors dimensions to obtain a Gold anchor record.

More modern metal anchors come in two main varieties - those that were designed to have a stock and those that were not. The later, stockless anchors can also be added to the database. Just make sure you enter your anchor into the right category – stocked or stockless.

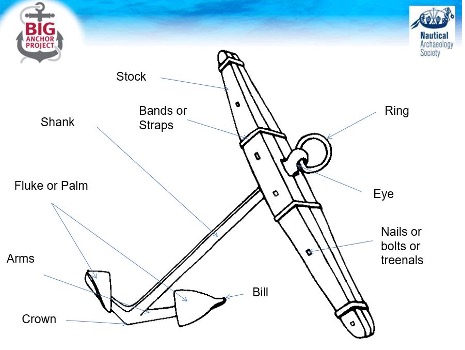

A stocked anchor is one that would have originally and may well still have a stock. The stock is the part of the anchor that is perpendicular (at 90 degrees) to the palms or flukes of the anchor. The stock served to lie flat on the seabed so that the one of the palms were forced to dig in and hold fast.

The stock might be made of wood - normally in multiple sections, or made of metal. The stock will either we clamped over the shank of the anchor or will pass through a hole in the shank. In some cases, the stock might also be missing, but the anchor will have clues to show you that it once did have a stock.

Above: An anchor in Portsmouth Dockyard with the stock clamped over the shank

Above: An anchor in Helsinki with the stock passing through a hole in the shank.

Above: A stocked admiralty longshank anchor, but without its stock. You can tell it was designed to have a stock as it has a stock key, projecting out of both sides of the shank – this would have helped locate and lock the stock in place.

Above: A stocked anchor photographed in Ireland, but without its stock. You can tell it was designed to have a stock as the shank has a hole near the end. This is the hole that the stock would have gone through and been locked in place, often with a locking or “cotter” pin.

The following document presents the basic ideal recording procedures needed for inclusion into the Big Anchor Project database. It is intended as a guide to help the recorder to gather information in a standard form so it can be used valuably in comparison with other similar data.

The first part of the procedures is concerned with general information providing contextual data, main features and a degree of confidence in the information. This type of information will be key for the various searches and manipulation of the anchor database. The second part of the procedures is meant to gather key dimensions of anchors and will help identify and confirm evolutionary characteristics.

A good selection of photographs with scale should complement any data recording. A preferred choice of photos is suggested in this guidance.

A stockless anchor is exactly as it sounds - an anchor which does not have or need a stock to work. Stockless anchors tend to be more modern, although of course you will see some vessels still using stocked anchors. They were designed to make it easier to recover from the seabed easier to store on the vessel.

A design and shape of a stockless anchor, especially the flukes is quite different compared to a stocked anchor and should be pretty obvious when you look at the anchor. Take a look at some of the stockless anchors below.

Above: A Hall’s improved stockless anchor was in use from 1910. This one belonged to the Union Castle Mail Ship Company (1857-1977) and is now on display outside the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London.

Above: A stockless anchor on display at the Den Helder Maritime Museum, in the Netherlands.

Above: A stockless anchor on display at Bari Port, Italy.

The following document presents the basic ideal recording procedures needed for inclusion into the Big Anchor Project database. It is intended as a guide to help the recorder to gather information in a standard form so it can be used valuably in comparison with other similar data.

The first part of the procedures is concerned with general information providing contextual data, main features and a degree of confidence in the information. This type of information will be key for the various searches and manipulation of the anchor database. The second part of the procedure is meant to gather key dimensions of anchors and will help identify and confirm evolutionary characteristics.

A good selection of photographs with scale should complement any data recording. A preferred choice of photos is suggested in this guidance.

Yes of course. Stone anchors were, almost certainly, the earliest type of anchor to be used, and continued in use for a very long time, indeed there are some types that are in use today. For this reason the dating of stone anchors is immensely difficult. Any dated examples are, potentially, of considerable importance so it is vital that any dating information be recorded. Most stone anchors are, in fact, composite anchors, in which the stone provided the weight to take the anchor to the sea bed, whilst the holding power was provided by means of separate arms, usually made of wood. Should any trace of the arms survive this too needs to be recorded.

Buoy and mooring anchors

Stone anchors were used for buoy and mooring anchors, usually simple weights, but it is possible that more complex types were used in the past.

Fishing gear

Stones have been, and in some places still are, used to sink nets, lines and other fishing gear. In many cases the only difference between these and some types of stone anchors is size, in fact it may be impossible to tell the difference between a large gear weight and a small boat anchor. Similar stones have also been used for more unusual purposes, such as driving fish into nets by beating them on the water. At present there is insufficient evidence to be able to separate these various uses of stone weights, for this reason all such stones, of whatever size, should be recorded.

Recycled stones

There is plenty of evidence that objects have been reused as stone anchors and fishing weights. This must be recognized as it could lead to problems when it comes to ascribing a date to an anchor, or recognizing an object as an anchor. Quern and mill stones can be recycled as anchors, so the discovery of such a stone on the sea bed need not be evidence of it having been carried as cargo.

Inscriptions

Stone anchors have been found with a variety of inscriptions, these range from an elaborate carving of an octopus to simple symbols. Carvings can sometimes provide evidence of date, a Christian cross, for example, must post date the introduction of Christianity to the area.

So far some five basic types of stone anchor have been recorded throughout the world. There are known variations to some of these forms, they usually take the form of additional, smaller holes. In many cases anchors can be made of either a naturally shaped stone, or a worked block.

There are many different types of stone anchor that reflect their function, but also their age and provenance (where they come from). They range from anchors with no holes that simply acted as a heavy weight to anchors with multiple holes that would have had wooden arms or spikes to stick in the seabed.

Anchor with no holes

A stone anchor without a hole drilled through it. It may have a groove cut around it (waisted). Stones of this type were sometimes used to weigh down a wooden anchor. Small versions were used as fishing weights and larger versions as buoy weights. Worked rectangular and rounded versions are known, as well as those based on an unworked stone.

Anchor with One hole

A stone anchor with a single hole through it. Also sometimes used to weigh down a wooden anchor. Smaller versions (maximum length 30 cm, weight less than 10 kg) are used as net-weights and very small examples (maximum length 12 cm, weight less than 500 g) as line-weights (dimensions taken from British examples).

Anchor with a Central hole

They can be found with a central hole these are sometimes called ‘ring anchors’. Quern and mill-stones can be recycled as anchors of this type. In eighteenth century Yorkshire, worn out mill stones were used as buoy anchors. Variations are known with smaller holes at the edge, either to attach the stone to a wooden anchor, or for a smaller rope to help in handling the anchor.

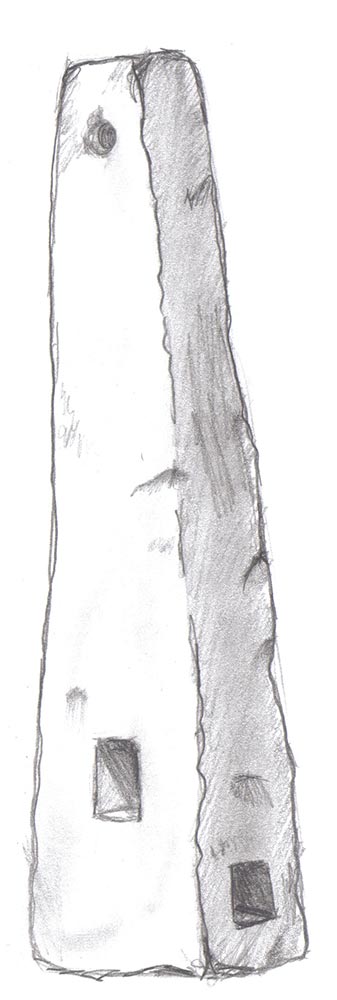

Anchor with a Hole at end

Single hole anchors are also found with a hole at one end: these are the earliest known forms of stone anchor, examples have been found in the eastern Mediterranean dated to the second millennium B.C. These have continued in use until the present day, and are one of the most common type of fishing weight. Variations are known with an additional hole drilled into the top of the stone, linking with the main hole. This is believed to have been for securing additional ropes to aid recovery and prevent loss.

Anchor with Two holes:

This type of anchor has two holes, one at each end of the stone. These anchors could be used in two ways, both of which are known from recent ethnographic examples. In the first example, one hole took a rope, the other an arm - usually of wood. In the second, only recorded on fishing gear, both holes took ropes. Wear-patterns on the stone should make it possible to distinguish which method was used.

Classical Anchor

This anchor was commonly used in the Mediterranean by both Greek and Roman shipping, though plenty of examples are know from the Atlantic, Red Sea and Indian Ocean. It is often referred to as a ‘classical’ or ‘Roman’ anchor, although evidence suggests that it continued in use for many centuries after the end of the Roman Empire. The holes form a triangle. The upper hole, which took the rope, can either be in the same plane as the lower holes or it can run across the stone. There are usually two lower holes (though three are known), always in the same plane. Rough examples, on flat slabs of stone, are probably ‘sand anchors’ designed to lie flat on a sandy seabed to achieve maximum grip.

Indian Ocean Anchor

This type is currently known from the Indian Ocean and Red Sea. It consists of a long stone block with the holes for the arms cut at 90o to one another. It is known to have been used during the medieval period, though when it was developed is unknown.

We have designed a recording form and written some guidance notes to show you what are the important features to note and which dimensions to measure that can then be uploaded into the project.

Download Recording Documents and Guides© Big Anchor Project 2018

Website and App by 3deep Media